I used to be a high school boys varsity basketball coach. In the beginning I brushed up on my knowledge by reading 3-4 books on basketball strategy and was a bit surprised at the varying approaches with regard to different levels of play. At the high school varsity level, we ran semi complicated plays. "You stand here. You go there. When that guy gets to you, you move to that position. Now pass him the ball." etc. I'd drill them over and over again so that when the game came, everyone knew what to do. When dealing with 17 year old boys, all of the plays dictated specific coordinated movements by each player, with minimal improvisation allowed by the players.

When you work with 14 year olds, or younger, the plays are much simpler, because they can't handle the complicated plays. As you get older, however, the plays get less and less rigid to the point when you reach the pro level there are very few actual plays, but rather simple guidelines that the players follow. Being professionals, the team relies on the players to make judgement calls on the court as they see fit.

What's That Got to do With Fighting?

Certain tactics will always beat other tactics provided that the fighters can handle the level of the tactic that is being asked to employ. The best fighters on the field know how to quickly read a situation, figure out when to engage and when to stall, can handle themselves out on their own, or know when they need to run and support a friend. The worst fighters on the field only know how to respond to a person directly attacking them, can handle simple commands like "charge," can't be relied on to perform specific jobs (like hold the left flank), and will die quickly if they are caught on the field with no support.

In a nutshell, lower level melee fighters need to stick together, usually in a shield wall formation, and charge in whatever direction they are told to charge. Higher level fighters can handle a more nuanced approach. Below I will talk about these approaches and how they theoretically play out with more advanced and less advanced fighters.

Echelon

This is a form of a diagonal attack. To be honest, this term was used by a friend I was fighting with today, and I have since looked it up and determined I didn't want to get bogged down with the technical definition of the word. For this purpose I'm using it to describe a sort of attack directed toward one side, often in a diagonal fashion.

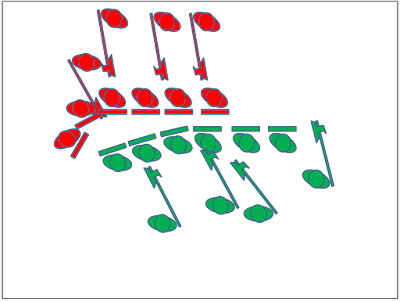

Today we discussed two approaches for this attack. The first is what I would describe as something that can be utilized by more advanced fighters. The leading flank of the attack goes fast and aggressive while the trailing flank of the attack merely has to deny the other side from attacking. They do this by attempting to stall the engagement, wheel away from the fighting, going on full defense, or using the feet to draw a bunch of fighters out. This is what it may look like:

Notice how green completely gave up their advantage by having their left flank plow straight into the center of red's shield wall. Here's another way to visualize the attack:

Every shield wall has a well defended front, with weakly defended flanks. The goal is to attack the enemy's flanks while defending your own.

When the trailing flank focusses on stalling the engagement in a "deny" role, green is able to attack red's weak flank while keeping its own flanks protected.

If green presses with its entire front, then neither side ends up with a positional advantage. Green has employed, at best, neutral tactics and hopes to win on skill and initiative alone.

Echelon With Newer Fighters

More advanced fighters should understand the nuances of an echelon charge with one flank on the attack and the other on a deny. They also should have no problems with controlled aggression. By controlled aggression, I mean being able to quickly decide when one needs to apply 100% pressure, and when one needs to pause to allow a friend to enter the fight, or to deny a position, etc.

These concepts are too complicated for newer fighters and can cause newer fighters to freeze up. Getting aggression levels up and committing to the attack are often more important goals for these fighters. Because of this, we often tell these fighters to "charge right" or "charge left" rather than to bother with the concept of a deny. As a result, the diagram above represents the lesser of two evils when compared to a group that denies left without ever full committing to the right:

Here you can see red putting itself in a better position to win because of green's lack of commitment to either side.

Think of it this way. Imagine red and green both as boxers. Red's commitment is to attack with the right hand and defend with the left hand. Green, on the other hand, commits only to defending with the left hand, but never commits to an attack with the right. Its only a matter of time before red wears green down. With newer fighters, you are basically teaching to just throw punches with both hands. I don't think that this should be the ultimate goal, but it is likely the best approach if dealing with a group of fighters that all have less than three years of moderate experience.

Besides, if this group runs into an evenly matched situation (ie they encounter another unit with less than three years of experience), they stand a better chance of winning.

A Slightly More Advanced Approach to the Full Charge

Since I began writing this blog post, I had another conversation with a veteran fighter and experienced tactician. He actually prefers the full charge rather than a press to one side and deny the other approach. The reasoning is that you still get an advantage by seizing the initiative, and that the fight ends in a quicker fashion and allows you to move on to other parts of the battle.

The problem left, however, is how to deal with an exposed flank on the trailing side. The answer is to bring fighters out of the back field to support (something that my unit did in last year's unbelted champions battle at Pennsic).

Summary

I've offered some different approaches to handling a small unit charge, though there are many more. My unit, Anglesey, is a very experienced unit that is very spear heavy. We tend to take a more fluid approach that involves spreading out and trying to break the fight down into smaller 2 on 1s and 3 on 2s, with the spears cleaning up.

Nevertheless, given the above approaches, I really prefer the first one that I laid out. Not everyone will be able to master it on the day of the fight, but I really do think its a goal to work toward. In our afternoon of fighting, it was the one approach that lead to our greatest degrees of success (75% of the unit still alive at the end of the battle).

I've offered some different approaches to handling a small unit charge, though there are many more. My unit, Anglesey, is a very experienced unit that is very spear heavy. We tend to take a more fluid approach that involves spreading out and trying to break the fight down into smaller 2 on 1s and 3 on 2s, with the spears cleaning up.

Nevertheless, given the above approaches, I really prefer the first one that I laid out. Not everyone will be able to master it on the day of the fight, but I really do think its a goal to work toward. In our afternoon of fighting, it was the one approach that lead to our greatest degrees of success (75% of the unit still alive at the end of the battle).