Introduction

Hello everyone, I'm THL Bari of Anglesey, squire to Sir William MacCrimmon, and one of the Lt Commanders for the East Kingdom. I've got decades of experience fighting and running melee practices in addition to a former career as a high school teacher and basketball coach. (Also, welcome to my 113th melee blog post!)

In this post I'm going to talk about methods of instruction, the scrimmage, the drill, and the lecture, and which methods are most useful for different kinds of situations. In short, sometimes you need to let people figure stuff out on their own, while other times that can be just too overwhelming for them.

Academy Award Winning Lectures

Walk into a school and observe a bunch of classrooms. The first door you open reveals an exciting teacher in the front of the room telling a story about the Battle of Gettysburg. The second door reveals a teacher saying, "Nine times seven," and the class repeats in unison, "Sixty Three." "Eight times four." "Thirty Two." And then you reach the third door and see a room full of kids with pencils in their hands scribbling onto paper with a teacher just watching. Every now and then the teacher will lean into a kid and say something that you can't quite make out.

The first room revealed an example of a lecture.

The second was an example of drills.

The third was an example of guided practice.

Robin Williams was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor in the movie Dead Poet Society. It was a movie full of scenes of him performing in front of a class, giving inspirational speeches, engaging students, getting them to think outside of the box, all while standing on top of his desk.

Would he have been nominated if he just walked around the room and occasionally leaned in and said, "Bill, you forgot to carry the one."

All three rooms revealed examples of teaching. However, as scadians, we've dedicated ourselves to a hobby which is centered around living in an alternate universe that we've created. We are, in a sense, thespians, and there's nothing exciting about watching our protagonist quietly standing off to the side and and allowing his or her class to work stuff out on their own. Williams would never have been nominated for that!

But it is still an important component of effective teaching.

The Optics of Teaching

The incentive for writing this post is that I've noticed from many different fighters a lack of understanding of the value of a scrimmage. For those not aware, a scrimmage is "practice play between two squads." There's this perception that if you are lecturing or running drills, then you are teaching. You know.....you're putting on the big performance, and everyone can see the teaching and the learning allegedly taking place. On the other hand, if a scrimmage is taking place, there is no performance by our protagonist, and there is no organized act put on by the students to signal to the audience, "Hey look, we are involved in a lesson." Despite its immense value, it doesn't LOOK like teaching, and I've noticed that sometimes teachers are afraid to just let their students fight.

Lectures, Drills, and the Value of Scrimmage

Let's take a simple melee concept that, here in the East, we call "forty-fives." When you have a 2v1 situation, the team of two should split, slightly, so that each fighter is attacking on an angle to get around their opponent's shield.

Do you understand the concept? I hope so, as I just communicated it to you through expository writing. If we were in person, I would have explained this to a group in a lecture format. In other words, the above was an example of the value of a lecture.

Now we can drill it. I can get a couple of lines of fighters going and have them attempt in engage a single enemy with this concept. This can be done in armor, out of armor, with weapons, without weapons, half speed, full speed, no contact, light contact, full contact, etc.

And then finally, we can test it in a scrimmage. In this case, we can run an 8v8 field battle and keep an eye out for whether or not people apply the technique within the context of a battle.

So the concept of 45s can be taught via lecture, through a series of drills, and within the context of a battle. There is an art to understanding when to use each teaching technique, how much time to spend on it, and which groups of fighters will benefit more from one method versus another. Some techniques, like running away from a legged fighter, don't need to be drilled at all (people already know how to run away) and only minimal time is needed to really explain the concept. This is definitely an example of something that can only really be learned through repetition during a scrimmage.

Lessons From a Basketball Practice

A long time ago a lightbulb went off during a basketball practice. My athletes were not "boxing out," after someone shot the ball (a technique used to put a player in position to get the rebound if the shot was missed). Despite running numerous drills to improve the technique, no one would use it during the scrimmage.

I eventually realized that the problem wasn't a lack of skill and technique. The problem was remembering to apply the technique during the chaos of a game situation.

The solution was to stop the play during a scrimmage whenever someone forgot to box out, draw everyone's attention to it, and then reset the play. I did this several times, and in a matter or minutes I was able to fix the problem. Not only was the scrimmage the best method to fix this particular problem, it was also the only method to identify the problem in the first place.

Application to Melee Practice

Two weeks ago I marshaled at a melee event with 100 fighters. We had a problem getting the fighters to stop during a hold. While most would stop fighting, there were often ~10-20 fighters who'd keep fighting after the hold was called.

The problem was that the fighters were not echoing the call of hold. A marshal can only yell so loud and needs the help of every fighter to echo the hold call until everyone has stopped fighting.

So, if we were to attempt to solve this problem at practice with instruction, we would say, "Okay, everyone, when I say hold, you say hold. Do you understand?" They nod heads, and you move on.

If we were to attempt to solve it with drills, a marshal would yell, "hold," and they'd respond, "hold." We could do that several times while they stand there in their armor. We could even correct the technique.

I'm being somewhat sarcastic. People already know how to say, "hold!" The issue is remembering to do it while fighting.

So to solve it in a scrimmage, you simply call a hold in the middle of a fight. While they are thinking about who they want to hit, and how they don't want to get stabbed, and whether or not they are nearing the battle goal, and while they are yelling commands, you yell, "hold!" And when they stand there and look at you, you ask, "what are you supposed to do in a hold?" "Stop fighting." "And?" "..........echo the command." "That's right. Reset the battle and do it again. Next time echo the command."

You can apply this to so many things. Keep in mind, however, that there needs to be a focus. Don't just call it for any mistake. You need to pick 1-3 things to focus on, and tell them in advance that that is what you are focussing on. It could be, for example, avoiding fighting legged fighters, or getting involved in a 1v1 fight in the middle of a field battle, or not echoing commands. Let them know that you'll be focussing on those three concepts, and if you catch someone doing it wrong, you'll call hold, point it out, and restart the battle.

Additional note: punishment isn't necessary. You only need a reinforcer. Calling hold and resetting the fight is enough reinforce the brain to pay attention to and internalize the practice goal.

Sage on the Stage vs Guide on the Side

Robin Williams in Dead Poet Society was the "sage on the stage," lecturing from the top of his desk. The "guide on the side" is the person that takes a step back and allows his or her students the chance to apply what they've learned, and to offer help only when needed.

Scadians (particularly the experienced ones) tend to be great lecturers. I mean that with sincerity and admiration as I've heard many great educational and inspirational lectures from long time veterans of the SCA.

But scadians also tend to be bad at sitting back and watching bad fighting. The fear is that if bad fighting is allowed to happen, then bad habits will form, and the fighters will actually get worse instead of better. I mean, would a trumpet teacher allow their students to play with bad technique?

Yes.

That's exactly what they do. They blow into their trumpet and play Twinkle Twinkle Little Star with the most wretched sound you've ever heard. They don't wait until they've received enough lecture to play it with a good sound, and they don't wait until they've mastered all of their scales (ie "do drills") until they are allowed to join an ensemble. They're taught a few basic concepts, do a few repetitions on it every day, and then show up to 4th period band practice and play really badly in a room full of other kids playing just as badly. And then, one at a time, little problems get fixed until, one day, enough problems have been fixed that they've become a good player.

Fighting melee isn't much different. Give them a little instruction. Give them some drills. And then let them go out and fight and make mistakes. Encourage the successes, fix the most egregious problems, ignore what you don't have time to work on, and take notes so that you can address large scale concepts at the next practice.

Learning by Doing

I've run a bunch of practices where I come in and think a) what these fighters need to work on, b) what are the best ways to work on these things and, c) will the buy into it, or will they revolt. Every practice will have a different set of fighters that must be carefully considered. What works for one group may fail spectacularly for another.

Having said that, if I do a good job of setting up the right scenario, I find that I may go through a practice doing virtually no teaching. I call lay on, and both teams will look pretty bad. When the scenario is over, I listen to one team and I hear, "we need to fix this and we need to do that better," and then I listen to the other team and hear them say the same thing. I stay out of their way and call lay on again. This time both teams do better.

Rinse and repeat. If anything, my job is to facilitate the learning and offering only what is needed while letting the fighters do as much for themselves as they can. The last thing I want is for the fighters to give up thinking for themselves and to just have me tell them what to do. Having said that, I will step in and fix something if they aren't fixing it themselves.

Clock Management

People should stop fighting at a melee practice because they ran out of energy, not because they ran out of time or because they stood too long in the sun. Every high school student teacher (a college student who is learning to become a high school teacher) has the same experience on their first day. They don't finish the lesson because they run out of time. We were actually taught to plan out our lesson segments and to keep a digital clock near us to pace the lesson. All instruction needs to be short and to the point. Don't worry if every last student didn't understand it by the end of your speech. The goal is not 100% understanding, but rather an introduction to the topic. I used to tell my students, "If you don't understand what to do when you start your problem, ask the kid to your left, and then ask the kid to your right. If the three of you still can't figure it out, then raise your hand and I'll come and help."

(Ironically this blog post ended up being much longer than I intended).

Mix Up the Scenarios

I've noticed a pattern. When you talk "melee" to a lot of people, they default right to single death field battles. I think this might be the closest thing we have to a melee version of a tourney format.

Do different things. Put all of the spears of one team. Do some rez battles. Do some 1v2s and 3v4s. Put all of the chiv onto the same team and give the other team more fighters.

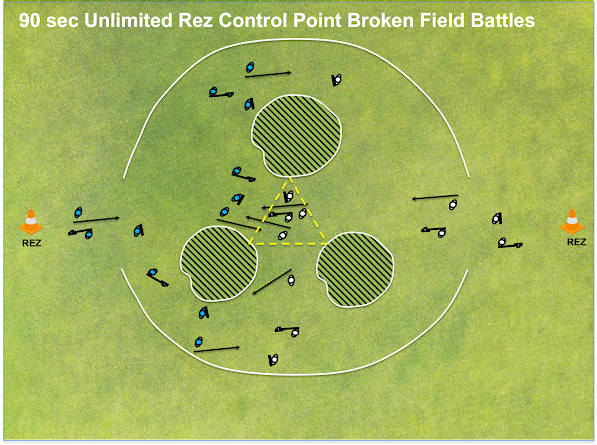

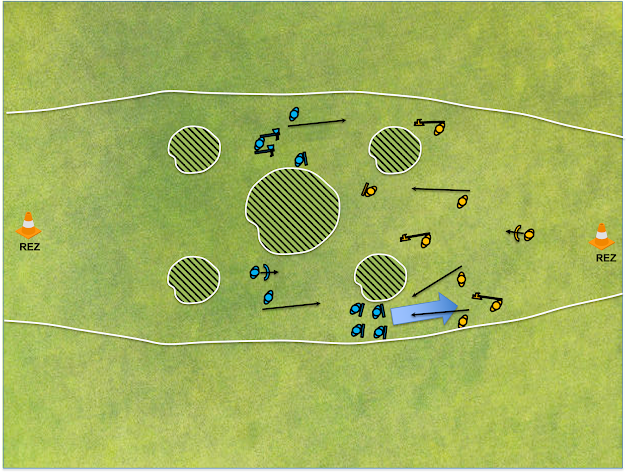

Right now, our fighters really seem to love broken field resurrection battles. Sometimes they get 3 lives and fight to the last one standing. Other times they'll have timed control points. This is really good for getting them to communicate and adjust tactics during a battle. Also, it's a lot of fun.

Oh, and of course, feel free to mix in some drills and lecture.

End of Practice Debrief

I stole this from our Northern Region practices, run by our current army general. At the end of practice, one at a time, allow each fighter to present what they liked about practice and what they think could be improved. It gets them to buy into and take ownership of the practice, lets them know that they are being heard, and provides valuable feedback to those who run the practice.

Read the Culture of the Practice

At the end of the day, a practice that no one returns to is not a very effective practice. That doesn't mean that you shouldn't try to steer the practice into a productive direction. Believe me, I've been to enough practices where culture is centered around people who talk a lot about fighting, but never actually want to fight. That's not something that I'm really interested in, and I try my best to either steer a practice into a direction of participation and productive learning, or I try to find a different avenue where I can create one.

But having said that, if your group wants drills and shy's away from live melee, then you may need to lean in that direction. If they feel like marching around the field in big blocks while listening to commands is a waste of their time, maybe decide if that can either be cut out, shortened, or if you can bargain with the fighters. "Hey, I know you don't like this, but as soon as this is done, I promise we'll run that scenario that you really love."

Summary

Ultimately you need to decide if a fighting deficiency is a practice priority or if there's something more important to work on. Then you need to decide if the issue is an inability to apply a skill, in which case you may need to run some drills, or if it's an inability to remember to apply the skill while fighting, in which case you'll need to figure out how to address it during a scrimmage. Make any lecturing purposeful, and try best to manage your time by talking while they're resting, not when they could be doing some drills or scrimmages.

And most importantly, whatever you do, make sure you get them to come back to the next one. If they aren't having fun or aren't feeling like they are getting something useful out of the practice, then they may not come back.